Music hall audiences had a reputation for rowdiness, often well deserved, as they didn’t attempt to hold back their feelings about an artiste. However this was mild compared to theatre in the Georgian period when the gentry would invade the stage during a performance causing the actors the indignity of elbowing their way to the front to say their lines. Spitting, bottle and orange peel throwing and sword-fighting were also audience pursuits, while the singing of popular songs competed with the thespians speaking from the stage. There was a fashion for the wealthier patrons to use their footman to save a seat, which meant the servant could be sitting next to ‘a lady of the first quality’ – just not done.

In the earlier part of the nineteenth century Song and Supper rooms in public houses, known as Free and Easies, were a form of popular entertainment. Entry was free but the audience were expected, nay encouraged, to buy alcoholic drink. Originally only men were admitted and the entertainment came from within the audience with amateur singers strutting their stuff. A reporter tells us ‘the entertainment given at these pothouses are of a low order. Songs are badly sung, mumbled or bawled with an ear–splitting accent.’ This didn’t put off the punters and gradually landlords added rooms for the entertainment nights which could be two or three times a week. The Free and Easies developed a reputation for drunkeness and bad behaviour. A letter to the Fleetwood Chronlcle in 1876 tells of the writer passing a Free and Easy in Blackpool ’out of which four boys were coming, and into which two were going; one of them was smoking a short pipe and the others were using profane language; the ages of these boys were from twelve and fourteen years.’ In the same year the chief constable of Preston described a Saturday night where five to six hundred young persons, half of them apparently under the age of sixteen, were to be found in a Free and Easy. Women and girls were now enjoying this kind of entertainment and young women would often take their babies. Groups of women, unaccompanied by men, were common with work-mates and neighbours meeting up for a good night out. The Manchester Evening News in 1877 reported the Chief Constable of that area proposed there should be Free and Easies without intoxicating drinks but which instead would sell cocoa. This seemed doomed to failure.

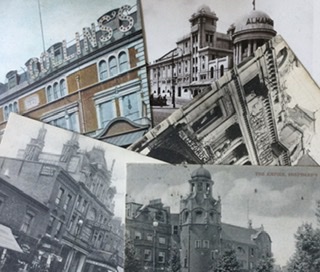

As the popularity of this form of entertainment grew the halls increased in size and professional acts were engaged. In the early halls the audience sat around tables, some facing away from the stage, and food and drink were served by waiters. There was much coming and going and the performer, without the luxury of a microphone, would battle to be heard above the general hubbub. Gradually music halls were built as separate buildings with audiences sitting in rows on various levels with bars for the the purchase of drinks. The main bar of the Metropolitan, Edgware, had a wide glass panel through which the entertainment could be viewed. The top tier, the gallery, was usually the rowdiest with the ’gallery boys’ hurling rotten fruit and veg, dead cats and even iron rivets at the stage to show their displeasure. The orchestra pit was often covered in wire netting to protect the musicians. The music hall managers were constantly engaged in trying to make their halls respectable with licence renewal a major worry. A contract from the Parthenon Music Hall Liverpool, signed by Adelaide and Oswald Stoll, contains the rule ’Every artiste must stringently avoid introducing any obscene Song, Saying or Gesture’. They were up against such reformers as Mrs Ormiston Chant who saw the halls as dens of depravity with predatory prostitutes and crude performers from whom the lower classes needed protection.

In 1909 the unfortunate Miss Charlesworth appeared at the Islington Hippodrome (later Collins), the Canterbury and the Paragon. On each occasion a gentleman introduced her and took a long time over it, to the displeasure of the audience. When Miss Charlesworth finally appeared she was greeted with a cacophany of boos and hisses and declared herself too nervous to to sing. She bowed to the audience before leaving the stage to the sound of sarcastic laughter. Fortunately this was not the experience of all music hall performers although their reception could vary from hall to hall. Marie Lloyd, much loved in London, was given an unenthusiastic reception in Bradford but gave as good as she got by not responding to an encore at the finish. TS Eliot noted that he had seen Nellie Wallace ’interrupted by jeering or hostile comment from a boxful of East-enders’ but he had never known Marie Lloyd to be confronted by hostility. He also notes that Nellie Wallace made a quick retort that silenced her hecklers.

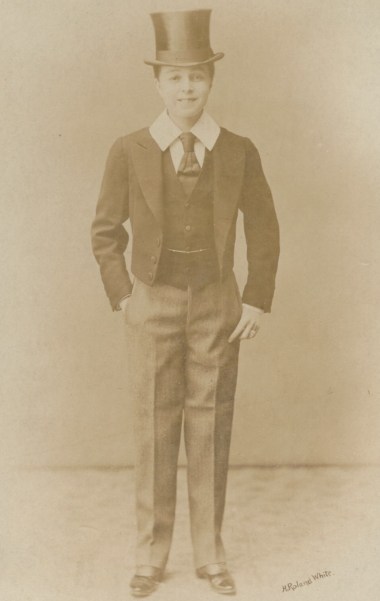

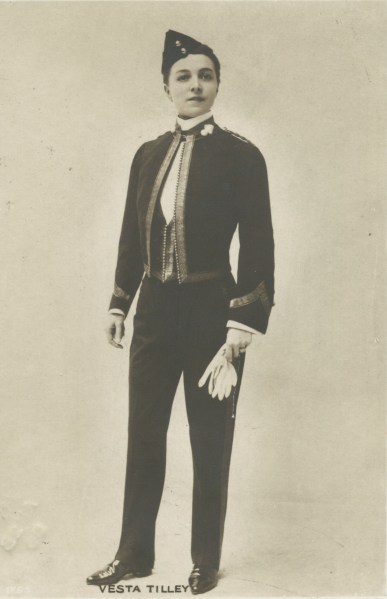

When postcards became the rage in the early 1900s music hall artistes were well represented and their fans collected the cards and sent them with messages of their everyday lives. In 1906 Mrs Baldwin hopes to see Vesta Tilley a week on Monday while a couple of years earlier Miss Gordon looked forward to seeing ’this Lady’ in all her latest successes. Ted saw Vesta Tilley at the Hippodrome (postmark blurred) and sends a card saying ’this girl was one of the soldiers who sang some songs.’ Ada Reeve is described as a nice girl – ‘not half’ by THH when writing to Miss Caley in 1905 and Florrie writes to Ethel to say she went to the Palace in Hull and bought the postcard of Gertie Gitana, ’the star artist.’ These audiences probably restrained themselves from throwing rotten food at the stage but showed their feelings nevertheless by joining in with chorus songs, wild applause and a bit of heckling. They had their favourites and sang and whistled their songs as they went about their business, secure in the feeling they had found a place where they belonged.

Thanks to the British Newspaper Archive, The Victorian Music Hall – Dagmar Kift

Marie Lloyd and Music Hall – Daniel Farson, Marie Lloyd – Richard Anthony Baker

The Popularity of Music Hall website

It held around 2000 people and had five bars, refreshment rooms, lounges and promenades, warehouses, stabling and a large open yard. Before the grand opening a journalist from the trade paper, the Entr’acte, remarked that the facilities for dispensing liquors are very considerable while an advert for musicians states that evening dress and sobriety are indispensable. There was to be an orchestra of eighteen musicians, all to be experienced in the variety and circus business, and a first violin, piano, cello and bassoon were needed to complete it. In July 1901 first-class acts of all kinds were directed to write immediately to secure their bookings.

It held around 2000 people and had five bars, refreshment rooms, lounges and promenades, warehouses, stabling and a large open yard. Before the grand opening a journalist from the trade paper, the Entr’acte, remarked that the facilities for dispensing liquors are very considerable while an advert for musicians states that evening dress and sobriety are indispensable. There was to be an orchestra of eighteen musicians, all to be experienced in the variety and circus business, and a first violin, piano, cello and bassoon were needed to complete it. In July 1901 first-class acts of all kinds were directed to write immediately to secure their bookings.

Daisy Jerome was born in the States in 1888 but moved to England as a child when her father suffered a financial crisis. Money was needed and she followed her sister on to the stage. She was a small, dainty figure with bright red hair, compelling eyes and an expressive face. Her appearance belied her risqué performances and her hoarse, sensual voice. She was a toe-dancer and a wooden shoe dancer, but best known as a mimic and comic singer. Daisy married Frederick Fowler in 1906 but they lived together for less than a year with Fowler blaming the marriage breakdown on the constant presence of his mother-in-law. He filed for divorce on the grounds of Daisy’s misconduct. She was living with Mr Cecil Allen in Battersea by this time and claimed Allen would marry her if she was divorced. The decree nisi was granted with Fowler saying he would shoot Allen if he didn’t marry Daisy. She left for a three year tour of Australia shortly after accompanied only by her mother. She adopted the name ‘the electric spark‘ and seems to have lived up to this in her public and private life.

Daisy Jerome was born in the States in 1888 but moved to England as a child when her father suffered a financial crisis. Money was needed and she followed her sister on to the stage. She was a small, dainty figure with bright red hair, compelling eyes and an expressive face. Her appearance belied her risqué performances and her hoarse, sensual voice. She was a toe-dancer and a wooden shoe dancer, but best known as a mimic and comic singer. Daisy married Frederick Fowler in 1906 but they lived together for less than a year with Fowler blaming the marriage breakdown on the constant presence of his mother-in-law. He filed for divorce on the grounds of Daisy’s misconduct. She was living with Mr Cecil Allen in Battersea by this time and claimed Allen would marry her if she was divorced. The decree nisi was granted with Fowler saying he would shoot Allen if he didn’t marry Daisy. She left for a three year tour of Australia shortly after accompanied only by her mother. She adopted the name ‘the electric spark‘ and seems to have lived up to this in her public and private life.