Kate Castleton was an early music hall performer and, as such, her formative years are difficult to trace. She was almost certainly born in 1856 in London and her last name was Freeman. There are varying accounts of her first name, the most common being Jennie, with Jane and May being other possibilities. Before she became a professional performer she said in a newspaper interview she worked in a factory making smoking-caps, was a member of a church choir and sang at temperance meetings. Information about this part of her life is hazy and the truth may have been given up for a story that would sit well with the public.

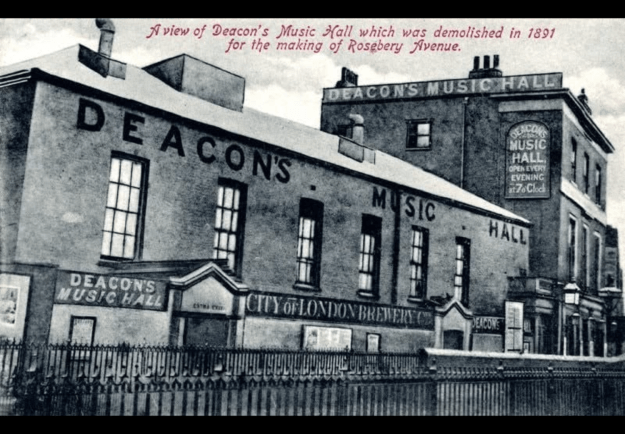

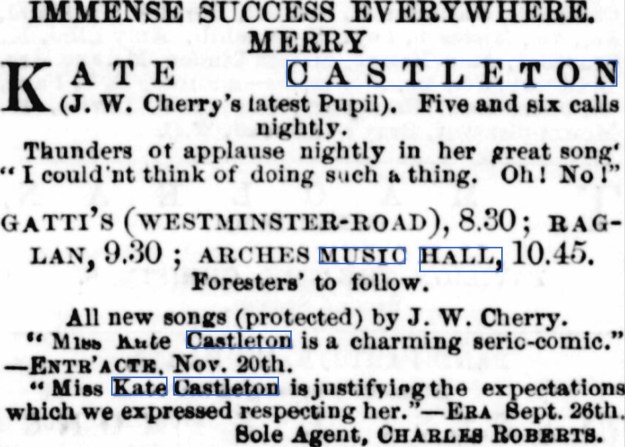

In 1875 there are accounts of her singing in the newly renovated Deacon’s Music Hall in Finsbury, London. She is described as a serio-comic with one rather patronising reviewer commenting, ‘in time, we should say that she will become popular.’ The trade paper, The Era, tells us Kate is nice-looking, wears good dresses and sings clearly and forcibly. She had been taken in hand by JW Cherry, a music teacher and composer of music hall songs. Mr Cherry was proud of his pupil and in 1876, during her Benefit at the London Alexandra Music Hall in the New Cut, he led her to the footlights where she was greeted with loud and protracted applause. The audience was known to be rowdy in that hall but her song Popsy-Wopsy found special favour and her dancing was said to be excellent. JW Cherry placed adverts in the trade papers offering tuition and boasted of Kate’s immense success everywhere.

However, in 1876 Kate was offered work in the States by Josh Hart who ran the Eagle Theatre in New York. On September 2nd 1876 JW Cherry put an angry notice in the Enr’acte, a trade paper, ending all contracts with Kate Castleton and stating his intention to divide her songs among his other pupils, taking away her right to sing them. She had unfinished business with Cherry and had not re-signed her contract with him. She could no longer sing songs such as Come Along, h’Isabella containing the lyrics ‘Come along h’Isabella, H’under me h’umbrella.’

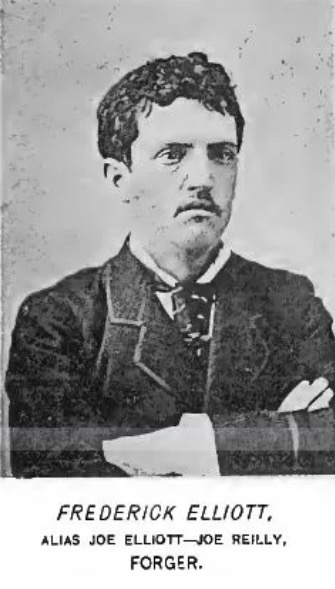

Kate started out at the Eagle Theatre and was a great success. One of her admirers was Joe Elliott, a forger, who had been in prison in more than one country and had a link with the murder of a fellow forger’s wife. She knew something of his criminal life but married him in the hope he would put it all behind him. The year after their marriage Elliott forged a draft for $64,000 on the New York Life Insurance Company. He was arrested but escaped and went to Boston where he stole $8,000 from a jeweller and was subsequently given a prison sentence of five years. Kate tried to secure his pardon but was unsuccessful. They lived together when Elliott came out of prison but soon divorced. They got back together and married again but in 1884 she was divorced again. Three days after getting this divorce she married Harry Phillips a theatrical manager. Phillips was her manager in the ‘musical plays’ she appeared in. In 1888 she was granted a divorce from Phillips on the grounds of his drunkenness and cruelty.

.

Kate had earned a good living in American theatre and bought two adjoining houses in Oakland, California in 1889. Her husband and some of his family lived in the larger house at the time of their divorce. They refused to leave and eventually Kate paid them to go – said to be $4,000. Kate’s family moved in, her sister occupying the smaller house, while Kate lived in a New York flat. In 1892 Kate died and various causes of death were given in newspaper obituaries. She was said to have died from a heart attack, peritonitis and death as the result of blood poisoning from a lotion used to treat sunburn. There is a strange addition to a report in an American newspaper reporting her death. It reads ‘Kate Castleton was never popular with professional people.’

Thanks to British Newspaper Archive, Ancestry, Monomania collection, Newspapers.com