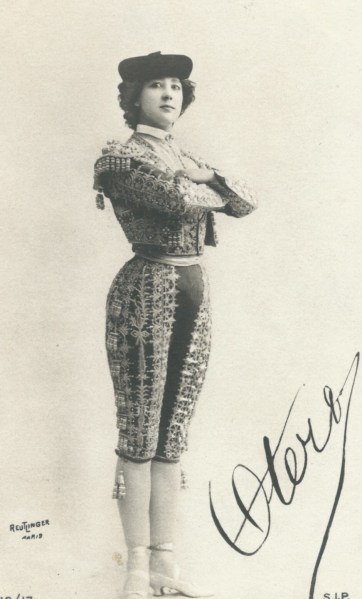

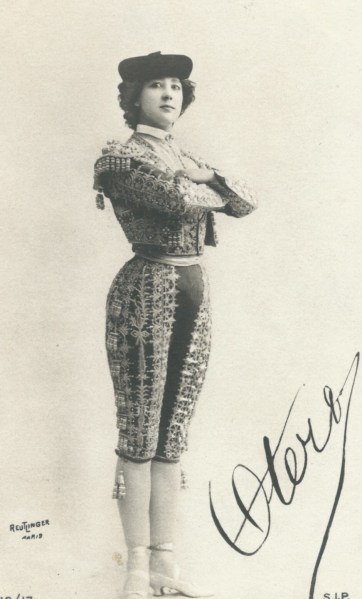

‘I was extraordinarily pretty’ states Caroline Otero in her autobiography My Story and this much is true. Music hall singer and dancer, courtesan and gambler, La Belle Otero lived a life of extremes and exaggerations that would raise eyebrows today. She claimed her mother was a beautiful Andalusian gypsy, Carmen, who danced, sang and told fortunes. Such was her beauty that a group of passers-by including a young Greek army officer, gazed at her in admiration as she was engaged in the unromantic task of hanging out the washing. The autobiography makes much of the courtship and devotion of the young man and tells of his death in a duel with Carmen’s lover. It is more likely La Belle Otero was born into a poor family in Galicia in November 1868 and given the name Augustina although she adopted the name Caroline at a young age. As a child she was sent away to work as a servant and is said to have been raped at the age of ten. It’s no wonder she gave herself a more romantic beginning.

‘I was extraordinarily pretty’ states Caroline Otero in her autobiography My Story and this much is true. Music hall singer and dancer, courtesan and gambler, La Belle Otero lived a life of extremes and exaggerations that would raise eyebrows today. She claimed her mother was a beautiful Andalusian gypsy, Carmen, who danced, sang and told fortunes. Such was her beauty that a group of passers-by including a young Greek army officer, gazed at her in admiration as she was engaged in the unromantic task of hanging out the washing. The autobiography makes much of the courtship and devotion of the young man and tells of his death in a duel with Carmen’s lover. It is more likely La Belle Otero was born into a poor family in Galicia in November 1868 and given the name Augustina although she adopted the name Caroline at a young age. As a child she was sent away to work as a servant and is said to have been raped at the age of ten. It’s no wonder she gave herself a more romantic beginning.

At thirteen or fourteen Caroline Otero seems to have run away with a young man  who found her work as a dancer in a Café. She moved up the scale from theatre to theatre, starring at the Folies Bergère , collecting and discarding admirers and lovers. It is said men fought duels over her and left themselves penniless after showering the object of their affection with flowers and jewels. A writer in The Sketch in 1898 reports that Mdlle Otero came on to the Alhambra stage in a salmon-pink dress covered in diamonds and turquoises with her fingers heavy with rings, the dress setting off her pale complexion and black hair to great advantage. The diamonds, worth millions of francs, were tokens of the esteem in which she was held by her admirers. The writer goes on to say that ‘most performers humbly seek the suffrages of their audience; La Belle Otero, whose equipment is in many respects inferior, from the artistic point of view, to that of her competitors, demands them as a right.’

who found her work as a dancer in a Café. She moved up the scale from theatre to theatre, starring at the Folies Bergère , collecting and discarding admirers and lovers. It is said men fought duels over her and left themselves penniless after showering the object of their affection with flowers and jewels. A writer in The Sketch in 1898 reports that Mdlle Otero came on to the Alhambra stage in a salmon-pink dress covered in diamonds and turquoises with her fingers heavy with rings, the dress setting off her pale complexion and black hair to great advantage. The diamonds, worth millions of francs, were tokens of the esteem in which she was held by her admirers. The writer goes on to say that ‘most performers humbly seek the suffrages of their audience; La Belle Otero, whose equipment is in many respects inferior, from the artistic point of view, to that of her competitors, demands them as a right.’

Otero was adept at self publicity and in 1902 the Paris correspondent of the Express writes that an engineer in Brussels was constructing an airship for her ‘by means of which she hopes to make a triumphal entry next August into Biarritz.’ She was worried it could be dangerous and so the balloon was to be dragged along by a car attached by a thin wire. If there was an accident she could ‘descend to the car by means of a rope ladder, which she will have tied in to the airship. The airship will float gracefully above the automobile at a height of 100ft.’ Mistress to ambassadors, princes, including the future Edward VII, and nobility throughout Europe, La Belle Otero scandalised and fascinated society in equal measure. Her weakness was gambling and she lost vast sums of money at the tables, sometimes her own and often her admirers’ fortunes. The Tatler tells us that in 1909 police raided a gambling club in Paris and found fifty women and ten men. On further investigation another woman, Caroline Otero, was found in a cupboard.

Otero was adept at self publicity and in 1902 the Paris correspondent of the Express writes that an engineer in Brussels was constructing an airship for her ‘by means of which she hopes to make a triumphal entry next August into Biarritz.’ She was worried it could be dangerous and so the balloon was to be dragged along by a car attached by a thin wire. If there was an accident she could ‘descend to the car by means of a rope ladder, which she will have tied in to the airship. The airship will float gracefully above the automobile at a height of 100ft.’ Mistress to ambassadors, princes, including the future Edward VII, and nobility throughout Europe, La Belle Otero scandalised and fascinated society in equal measure. Her weakness was gambling and she lost vast sums of money at the tables, sometimes her own and often her admirers’ fortunes. The Tatler tells us that in 1909 police raided a gambling club in Paris and found fifty women and ten men. On further investigation another woman, Caroline Otero, was found in a cupboard.

Liane de Pougy

Stories were rife of her exploits including a report in a Mexican newspaper that Otero had shot a love rival, Liane de Pougy, through the heart. Liane de Pougy was another famous courtesan and actress of the day. Both ladies were said to be very much amused by the report. In 1907 she insured her ankles for £15,000 each and was advertised as the only dancer with ankles worth £30,000. She was not universally admired and in 1895 the Evening Telegraph and Star reported a court case from Paris concerning the notorious Otero. She was living in an apartment in the Rue Charron rented by her English friend, Mr Bulpett, and the landlord charged him with not fulfilling the terms of the lease, namely that the apartment should be kept in a respectable manner. The landlord claimed Otero was damaging to the value of his property as other people objected to her. Two other tenants had signed a petition saying if she did not move they would break their leases. The defence denied any scandal had been caused by Otero’s presence in the apartments and that she and Mr Bulpett had as much right as other tenants to give dinners, hold receptions, have a carriage at the door and live a life of luxury. The judgement was in favour of Mr Bulpett.

The author, Colette, knew Otero when the great dancer was in her forties and describes her in My Apprenticeships as dancing and singing for her guests for up to four hours and having a body that had ‘defied sickness, ill-usage and the passage of time.’ The character of Lea in Colette’s novel Chéri is largely based on Otero and her lifestyle.

La Belle Otero retired after the First World War having built up a vast fortune but her love of gambling was to be her undoing and she died in relative poverty in 1965 at the age of 96. The Tatler had rather prematurely announced her death in 1947. Her autobiography is a ripping yarn rather than a factual account but she had a sensational life and career and who can deny her a little economy with the truth.

Thanks to the British Newspaper Archive, My Story – La Belle Otero,

My Apprenticeships – Colette

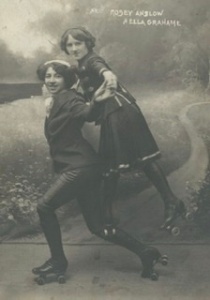

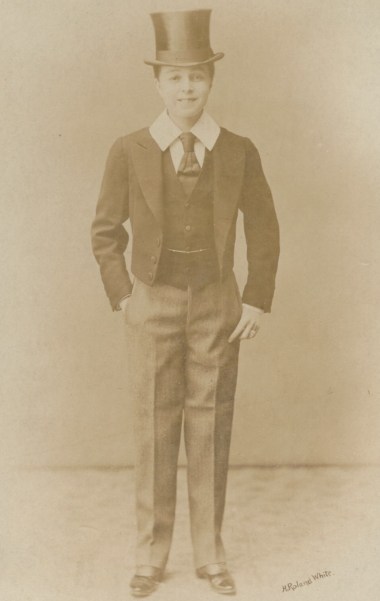

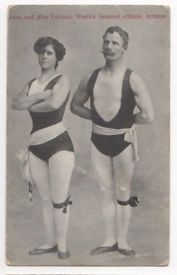

Dolly Mitchell was a young Scottish roller-skater who teamed up with her American teacher, Harley Davidson, to give displays in rinks and music halls. Advertised as the greatest skaters in the world and giving a wonderful exhibition of trick, fancy, acrobatic, graceful and artistic skating. They displayed over £1,000 worth of gold and diamond medals won in competition

Dolly Mitchell was a young Scottish roller-skater who teamed up with her American teacher, Harley Davidson, to give displays in rinks and music halls. Advertised as the greatest skaters in the world and giving a wonderful exhibition of trick, fancy, acrobatic, graceful and artistic skating. They displayed over £1,000 worth of gold and diamond medals won in competition and had this publicity photo taken by Léo Forbert’s studio in Warsaw. Ella writes on the back of the card ‘

and had this publicity photo taken by Léo Forbert’s studio in Warsaw. Ella writes on the back of the card ‘

with a barrel organ. The card on the barrel organ reads ‘Molly O’Morgan’. The young woman is staring out from the photograph as if she has a story to tell. There is a story of Molly O’Morgan, the daughter of an Irish mother and an Italian organ-grinder father, who had dark brown hair and laughing eyes. It is said her mother died when Molly was young and she and her father left Ireland with a barrel organ and monkey to take their chances in Europe. Molly would dance while her father played the barrel organ and the crowds were charmed into parting with their coins. They travelled from city to city and eventually arrived in Monte Carlo where Molly’s fortunes changed. She was noticed by Duke Medici-Sinelli, an elderly widower, who naturally enough was also rich and charming. The Duke arranged for Molly to appear at a theatre and in the way of fairy tales she immediately became a star. Molly and the Duke married and unkind rumours suggested she was a gold-digger although the couple seemed devoted to each other. When the Duke died Molly did not marry again but came to Monte Carlo every year and stayed in the same suite in which she and the Duke had spent their honeymoon. She was said to live in Hungary with a distant branch of the Duke’s family.

with a barrel organ. The card on the barrel organ reads ‘Molly O’Morgan’. The young woman is staring out from the photograph as if she has a story to tell. There is a story of Molly O’Morgan, the daughter of an Irish mother and an Italian organ-grinder father, who had dark brown hair and laughing eyes. It is said her mother died when Molly was young and she and her father left Ireland with a barrel organ and monkey to take their chances in Europe. Molly would dance while her father played the barrel organ and the crowds were charmed into parting with their coins. They travelled from city to city and eventually arrived in Monte Carlo where Molly’s fortunes changed. She was noticed by Duke Medici-Sinelli, an elderly widower, who naturally enough was also rich and charming. The Duke arranged for Molly to appear at a theatre and in the way of fairy tales she immediately became a star. Molly and the Duke married and unkind rumours suggested she was a gold-digger although the couple seemed devoted to each other. When the Duke died Molly did not marry again but came to Monte Carlo every year and stayed in the same suite in which she and the Duke had spent their honeymoon. She was said to live in Hungary with a distant branch of the Duke’s family.

‘I was extraordinarily pretty’ states Caroline Otero in her autobiography My Story and this much is true. Music hall singer and dancer, courtesan and gambler, La Belle Otero lived a life of extremes and exaggerations that would raise eyebrows today. She claimed her mother was a beautiful Andalusian gypsy, Carmen, who danced, sang and told fortunes. Such was her beauty that a group of passers-by including a young Greek army officer, gazed at her in admiration as she was engaged in the unromantic task of hanging out the washing. The autobiography makes much of the courtship and devotion of the young man and tells of his death in a duel with Carmen’s lover. It is more likely La Belle Otero was born into a poor family in Galicia in November 1868 and given the name Augustina although she adopted the name Caroline at a young age. As a child she was sent away to work as a servant and is said to have been raped at the age of ten. It’s no wonder she gave herself a more romantic beginning.

‘I was extraordinarily pretty’ states Caroline Otero in her autobiography My Story and this much is true. Music hall singer and dancer, courtesan and gambler, La Belle Otero lived a life of extremes and exaggerations that would raise eyebrows today. She claimed her mother was a beautiful Andalusian gypsy, Carmen, who danced, sang and told fortunes. Such was her beauty that a group of passers-by including a young Greek army officer, gazed at her in admiration as she was engaged in the unromantic task of hanging out the washing. The autobiography makes much of the courtship and devotion of the young man and tells of his death in a duel with Carmen’s lover. It is more likely La Belle Otero was born into a poor family in Galicia in November 1868 and given the name Augustina although she adopted the name Caroline at a young age. As a child she was sent away to work as a servant and is said to have been raped at the age of ten. It’s no wonder she gave herself a more romantic beginning. who found her work as a dancer in a Café. She moved up the scale from theatre to theatre, starring at the Folies Bergère , collecting and discarding admirers and lovers. It is said men fought duels over her and left themselves penniless after showering the object of their affection with flowers and jewels. A writer in The Sketch in 1898 reports that Mdlle Otero came on to the Alhambra stage in a salmon-pink dress covered in diamonds and turquoises with her fingers heavy with rings, the dress setting off her pale complexion and black hair to great advantage. The diamonds, worth millions of francs, were tokens of the esteem in which she was held by her admirers. The writer goes on to say that ‘most performers humbly seek the suffrages of their audience; La Belle Otero, whose equipment is in many respects inferior, from the artistic point of view, to that of her competitors, demands them as a right.’

who found her work as a dancer in a Café. She moved up the scale from theatre to theatre, starring at the Folies Bergère , collecting and discarding admirers and lovers. It is said men fought duels over her and left themselves penniless after showering the object of their affection with flowers and jewels. A writer in The Sketch in 1898 reports that Mdlle Otero came on to the Alhambra stage in a salmon-pink dress covered in diamonds and turquoises with her fingers heavy with rings, the dress setting off her pale complexion and black hair to great advantage. The diamonds, worth millions of francs, were tokens of the esteem in which she was held by her admirers. The writer goes on to say that ‘most performers humbly seek the suffrages of their audience; La Belle Otero, whose equipment is in many respects inferior, from the artistic point of view, to that of her competitors, demands them as a right.’  Otero was adept at self publicity and in 1902 the Paris correspondent of the Express writes that an engineer in Brussels was constructing an airship for her ‘by means of which she hopes to make a triumphal entry next August into Biarritz.’ She was worried it could be dangerous and so the balloon was to be dragged along by a car attached by a thin wire. If there was an accident she could ‘descend to the car by means of a rope ladder, which she will have tied in to the airship. The airship will float gracefully above the automobile at a height of 100ft.’ Mistress to ambassadors, princes, including the future Edward VII, and nobility throughout Europe, La Belle Otero scandalised and fascinated society in equal measure. Her weakness was gambling and she lost vast sums of money at the tables, sometimes her own and often her admirers’ fortunes. The Tatler tells us that in 1909 police raided a gambling club in Paris and found fifty women and ten men. On further investigation another woman, Caroline Otero, was found in a cupboard.

Otero was adept at self publicity and in 1902 the Paris correspondent of the Express writes that an engineer in Brussels was constructing an airship for her ‘by means of which she hopes to make a triumphal entry next August into Biarritz.’ She was worried it could be dangerous and so the balloon was to be dragged along by a car attached by a thin wire. If there was an accident she could ‘descend to the car by means of a rope ladder, which she will have tied in to the airship. The airship will float gracefully above the automobile at a height of 100ft.’ Mistress to ambassadors, princes, including the future Edward VII, and nobility throughout Europe, La Belle Otero scandalised and fascinated society in equal measure. Her weakness was gambling and she lost vast sums of money at the tables, sometimes her own and often her admirers’ fortunes. The Tatler tells us that in 1909 police raided a gambling club in Paris and found fifty women and ten men. On further investigation another woman, Caroline Otero, was found in a cupboard.

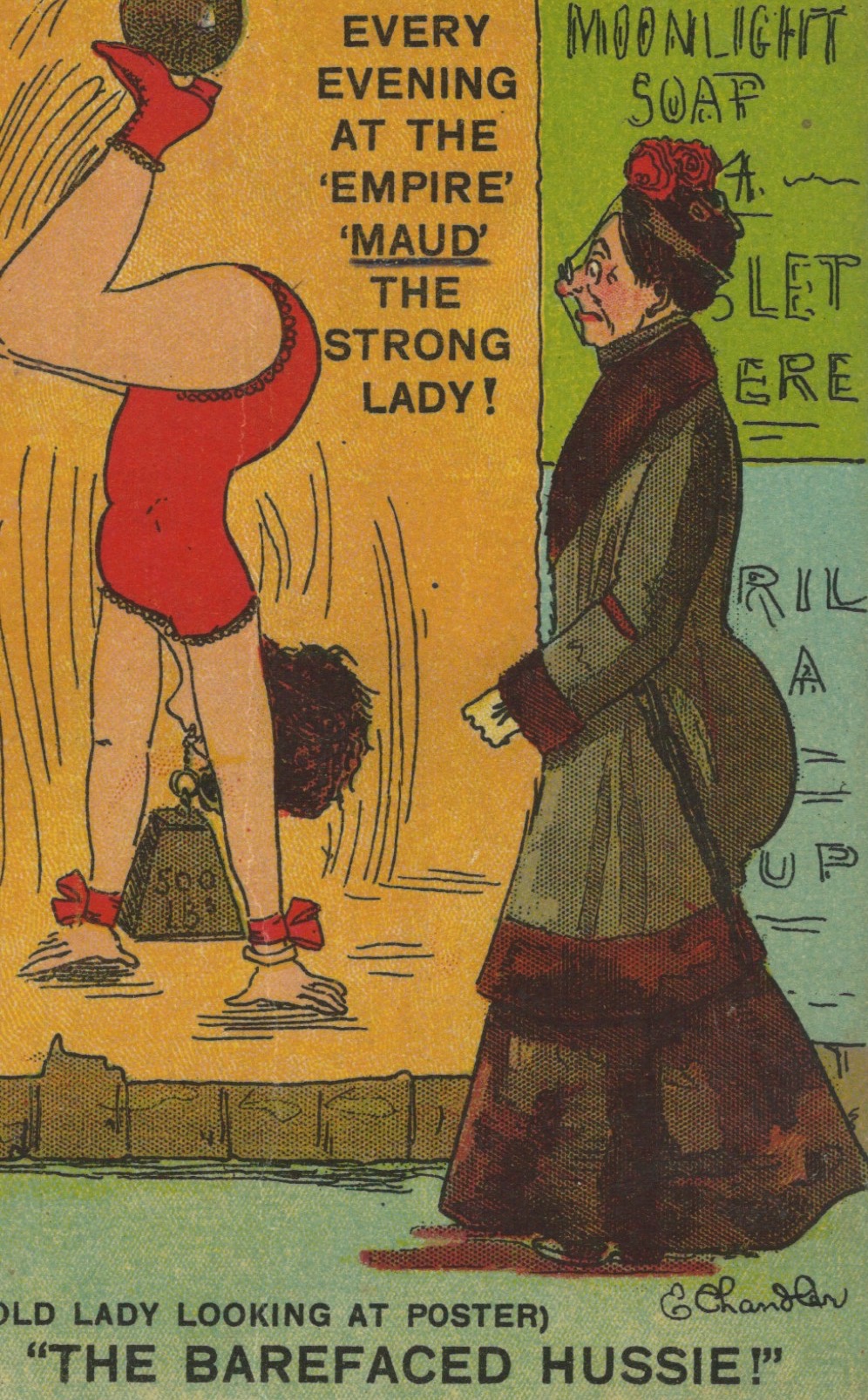

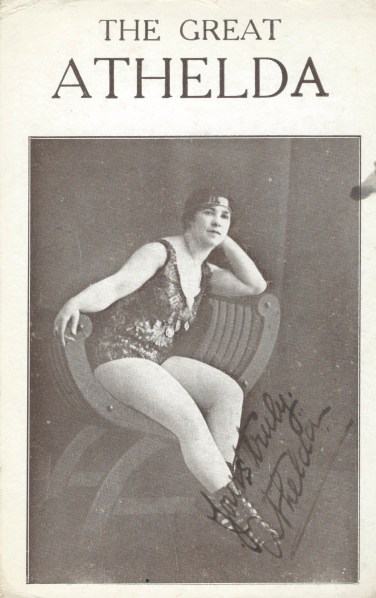

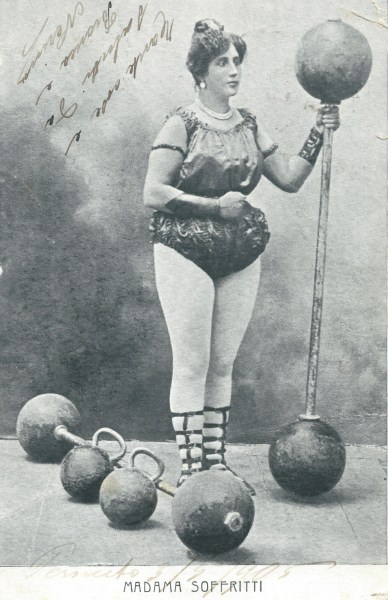

In Victorian and Edwardian society women were often portrayed as the weaker sex but music hall was another world altogether and audiences flocked to see women of prodigious strength full of confidence in themselves and their right to perform. One such was the Great Athelda, born Frances Rheinlander in Manchester, who performed on the music hall stage from around 1912. Athelda was reported to have made her debut in Buenos Aires in December 1911. She was also known as the miniature Lady Hercules and Britain’s Beautiful Daughter.

In Victorian and Edwardian society women were often portrayed as the weaker sex but music hall was another world altogether and audiences flocked to see women of prodigious strength full of confidence in themselves and their right to perform. One such was the Great Athelda, born Frances Rheinlander in Manchester, who performed on the music hall stage from around 1912. Athelda was reported to have made her debut in Buenos Aires in December 1911. She was also known as the miniature Lady Hercules and Britain’s Beautiful Daughter.

It held around 2000 people and had five bars, refreshment rooms, lounges and promenades, warehouses, stabling and a large open yard. Before the grand opening a journalist from the trade paper, the Entr’acte, remarked that the facilities for dispensing liquors are very considerable while an advert for musicians states that evening dress and sobriety are indispensable. There was to be an orchestra of eighteen musicians, all to be experienced in the variety and circus business, and a first violin, piano, cello and bassoon were needed to complete it. In July 1901 first-class acts of all kinds were directed to write immediately to secure their bookings.

It held around 2000 people and had five bars, refreshment rooms, lounges and promenades, warehouses, stabling and a large open yard. Before the grand opening a journalist from the trade paper, the Entr’acte, remarked that the facilities for dispensing liquors are very considerable while an advert for musicians states that evening dress and sobriety are indispensable. There was to be an orchestra of eighteen musicians, all to be experienced in the variety and circus business, and a first violin, piano, cello and bassoon were needed to complete it. In July 1901 first-class acts of all kinds were directed to write immediately to secure their bookings.