This is an amended version of my original post on Maggie Duggan as a reader has very kindly given me the correct information about her birth. She doesn’t have a birth record at the General Register Office in London, which was common amongst poorer families. She was born in Liverpool in 1857 and not 1860 as I had thought. The 1861 census shows her family living at 47 Blenheim Street in Liverpool. Her mother, Mary, is listed as the head of the household and as a sailor’s wife. Maggie was six months old and her sister, Sarah, was nine. Both Mary and Sarah have their place of birth listed as Ireland which could explain the later confusion over Maggie’s birthplace and accent when she was on the stage.

In an interview in the trade magazine, The Era, Maggie revealed she made her first appearance in a pantomime in her early childhood at the Adelphi Theatre, Liverpool. Her salary was three shillings a week and she was expected to provide her own boots. She disagreed with people who thought it wrong that children should act in pantomime saying ‘Tis very often delightful to the youngsters – – pantomime children are very often taken from poverty-stricken surroundings and taught the rudiments of an art that may bring them fame and fortune.’ The interviewer saw this as her opinion but it could have been her own experience.

Maggie Duggan travelled as a member of a ballet troupe and then took the giant step of moving to the Cape as part of a theatre group. On arrival, she had trouble learning her lines and was so bad the manager declared he would send her home by the same boat that had brought her out. She persevered and added a hornpipe to her role which was so well received she stayed on and was at the Cape for two years. On her return to England she worked with burlesque and comic opera companies where she performed ‘breeches parts’ saying that she would feel dreadfully ill at ease in petticoats. The newspaper article is careful to add ‘that is, of course, on the stage.’ She thought a woman of her size looked ungainly in skirts on the stage.

There is a confusing remark from Maggie Duggan that the heroes of musical comedy were all played by men and, although she loved that kind of entertainment, she was looking for something different. Does this make sense after the breeches roles? Perhaps they were all burlesque. Maggie made a big splash with the Gaiety company in the second outing of the burlesque, Cinder-Ellen Up Too Late, taking the part of the Prince of Belgravia previously played by a man. During the performance she sang two music hall songs – The Man who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo and The Rowdy-Dowdy Boys.The first of these had been plugged by Charles Coburn at The Oxford but when Maggie Duggan sang it Charles Coburn’s share of the royalties rose to £600. The other song was a music hall hit for Millie Hylton.

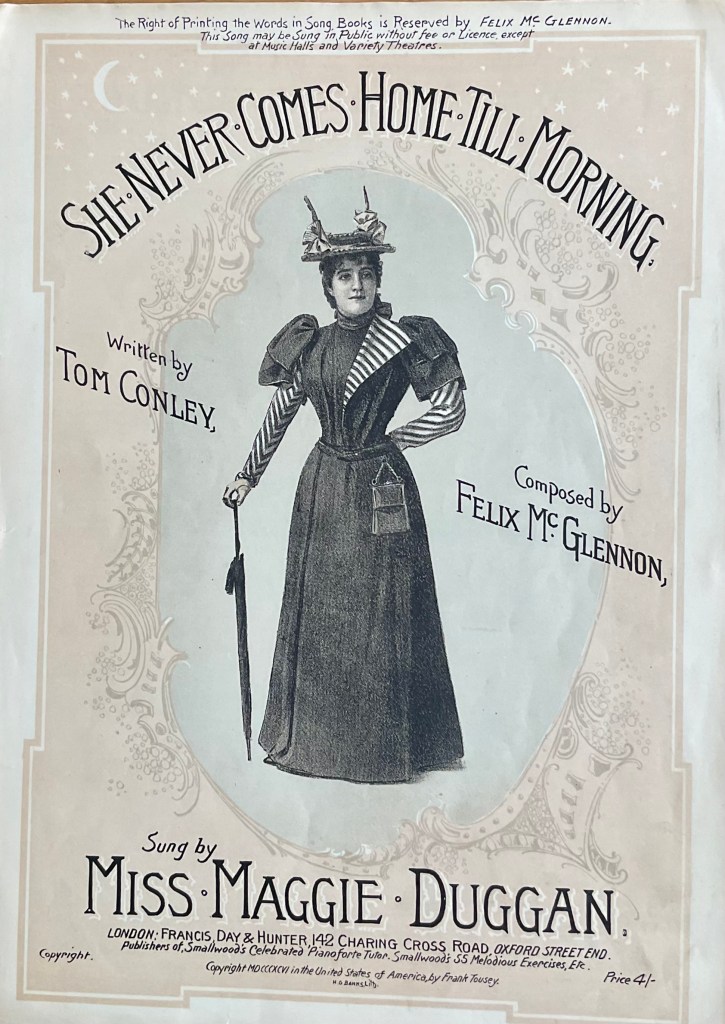

The popularity of these songs may have finally decided Maggie Duggan to switch to music hall, although it wasn’t always easy. She lamented the lack of good songs saying she could buy a hundred and just find one worth singing. In 1900 there is an advert in the Music Hall and Theatre Review placed by Maggie Duggan requesting good low comedy and character songs. She found the lack of rehearsal in music halls equally hard as the band could often be at cross purposes with the singer during a performance. Also, in her previous career she was better known on the provincial stage and worried it would be hard to get work in London halls.

This may have been unfounded as in 1894 we find in The Era that she moved from Birmingham to the London Alhambra and ‘other west end halls.’

Maggie Duggan excelled in pantomime with her height and build making for an excellent principal boy. She was in demand in Leeds, Manchester, Liverpool and, perhaps best for her career, Drury Lane. Ada Reeve in her autobiography, Take it For a Fact, talks about working with her in Little Boy Blue in 1893. Maggie Duggan played her role as principal boy ‘in the dashing, strutting manner peculiar to those days. Her trademark was a diamond butterfly which she wore pinned to her tights on her thigh.’

In June 1905 a headline in the London Morning Leader proclaimed in heavy type, Bigamy with Maggie Duggan. The court case was brought by Mrs Amy Ward against her husband, Thomas William Ward, and she asked for the dissolution of her marriage which had taken place in 1892. The couple separated in 1895 and Amy Ward alleged her husband was guilty of desertion, bigamy and misconduct. She had recently discovered her husband had entered into a bigamous marriage with Maggie Duggan. The petitioner had her watched when she was appearing at the Tivoli Music Hall, Manchester, and discovered that she and the respondent were living as man and wife. Mr Ward admitted the bigamous marriage but had been under the impression his wife was dead. Maggie Duggan was a widow when she married Mr Ward who had shown her a newspaper advertisement which she believed to be a notice of the death of his former wife. Mrs Ward obtained a degree nisi with costs.

Maggie Duggan died in 1919 in the Liverpool workhouse infirmary from bronchial pneumonia accelerated by alcohol. She was sixty years old and had retired from the stage some fifteen years earlier.

Thanks to The British Newspaper Archive, Monomania archive, Winkles and Champagne -Wilson Disher, Take it for a Fact -Ada Reeve

Many thanks to Raymond Crawford who took the trouble to read the post and contact me with the correct information.

.

Ada Reeve was born in London in 1874 into a theatrical family and she made her debut at the age of four in the pantomime Little Red Riding Hood at the Pavilion Theatre, Whitechapel. Using the name Little Ada Reeve she continued to appear in plays and pantomime to great acclaim. Her elocution was said to be ‘peculiarly free from Cockney taint.’ In an advertisement in the trade paper, the Era, in May 1884 Little Ada Reeve announced she was at liberty for speciality and Christmas for the principal child’s part and was said at ten years of age to be a singer, actress, dancer, reciter and drum soloist.

Ada Reeve was born in London in 1874 into a theatrical family and she made her debut at the age of four in the pantomime Little Red Riding Hood at the Pavilion Theatre, Whitechapel. Using the name Little Ada Reeve she continued to appear in plays and pantomime to great acclaim. Her elocution was said to be ‘peculiarly free from Cockney taint.’ In an advertisement in the trade paper, the Era, in May 1884 Little Ada Reeve announced she was at liberty for speciality and Christmas for the principal child’s part and was said at ten years of age to be a singer, actress, dancer, reciter and drum soloist.

Ada Reeve continued to work as an actress on stage and in film. Her last stage role was at the age of eighty and she appeared in her last film at the age of eighty-three. She died in 1966 at the age of ninety-two. She had that special something which audiences responded to and in this clip we can see that charm and hear that voice, still clear in her eighties. She is talking to Eamonn Andrews after an appearance on the television show This is your life.

Ada Reeve continued to work as an actress on stage and in film. Her last stage role was at the age of eighty and she appeared in her last film at the age of eighty-three. She died in 1966 at the age of ninety-two. She had that special something which audiences responded to and in this clip we can see that charm and hear that voice, still clear in her eighties. She is talking to Eamonn Andrews after an appearance on the television show This is your life.