She was ‘only a ballet girl’ was a term often used in theatre circles to cover everyone from the flying fairy to the corps de ballet and its principal dancer. Ballet girls were seen as having easy morals and were treated with scant respect. Albert Smith in the Natural History of the Ballet Girl, published 1847, points out that a gent imagines he has but to wink at a fairy on stage to be immediately received as her accepted admirer. Ballet girls were employed in large numbers to look decorative as well as to dance and would often be placed as ‘extras’ around the stage. Their dancing skills were often found wanting. Opera and pantomime were originally a good source of employment for them and in 1877 Davenport & Wright, Musical and Dramatic Agency, required 150 young attractive ballet ladies for pantomimes in London and the provinces. Music hall managers, always looking for something new, began to stage ballets as part of their programme and in 1866 the Canterbury Music Hall in London advertised a grand ballet spectacle with a fairy orchestra and upwards of fifty ballerinas.

The ballet girls were often mocked for their lack of training and poor skills but it was a hard life with little romance. In the 1860s a dancer paid for her own petticoat, tights, fleshings (flesh coloured tights) and shoes and much time was spent repairing and re-covering worn shoes. Wages were low and sometimes dancers were not paid for rehearsals, which were long with only an hour or two off before the evening performance. This could last until midnight and occasionally a rehearsal could be called after the performance. Those in the front line were paid more than those at the back so competition was fierce with ballet girls dreaming of working their way through the ranks to become principal dancer or coryphée. Things had improved a little by the end of the nineteenth century but dancers were still responsible for buying their own shoes and tights and were encouraged to take professional dance lessons at their own expense.

It could be a dangerous occupation with newspaper reports of dancers sustaining serious burns when costumes caught fire when moving too close to, or falling into, the limelights along the edge of the stage. They ran the risk of scenery falling on them and those dancers propelled from beneath the stage fervently hoped the star trap would open for them to make their dramatic appearance. The vagaries of the licensing laws were also a problem. In Edinburgh, Henry Levy applied to renew the license for the Southminster Music Hall in 1872. A petition had been received from ninety-five working men who were dissatisfied with the entertainments provide by the Southminster with many of the songs and dances being of a mischievous and immoral tendency – – also of a significantly suggestive character, exercising a corrupting influence on the young of both sexes who so largely frequent this place of amusement. The can-can ballet was their main target which had been put on nightly for a few months and enjoyed by the gallery boys and girls. The license was renewed on the understanding that the can-can would no longer feature in the programme.

The status of ballet changed over the years but music hall kept it alive and introduced audiences to a a different form of entertainment. In 1870 the burlesque actress and music hall star Nelly Power appeared at the Canterbury Hall, London, in a Grand Ballet entitled Four-leaved Shamrock. She played the roles of several characters and imitated the most popular comic songs of her day – with no advance in the prices. The London halls, the Empire and the Alhambra were renowned for their ballets which took over one half of the programme. We can assume there was a rivalry between the two as a former Alhambra dancer opined they were expected to dance, unlike the corps de ballet of the Empire, who merely held up the scenery. The managers of these two halls became aware of the Diaghilev Ballet and the attraction of supremely talented artistes. The Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova and the Danish Adeline Genée were engaged and changed the public opinion of ballet forever.

Thanks to The British Newspaper Archive, vintagepointe.org, The Natural History of the Ballet Girl -Albert Smith, My theatrical and Musical Recollections – Emily Soldene, Monomania collection.

Minnie Cunningham was a music hall singer and dancer, best remembered for featuring in a painting by Walter Sickert. She was born in Birmingham in 1870, the daughter of music hall comic singer Ned Cunningham. He was well-loved and successful, being described by the Birmingham Gazette as the ‘greatest comic singer in the world.’ His daughter started her music hall career after his death when she was ten years old. Minnie Cunningham tells us she began as a male impersonator and sang her father’s songs, although reviews of the time don’t mention male impersonation, only her singing and dancing. She moved from the provincial halls to London where she performed at the principal halls of the day.

Minnie Cunningham was a music hall singer and dancer, best remembered for featuring in a painting by Walter Sickert. She was born in Birmingham in 1870, the daughter of music hall comic singer Ned Cunningham. He was well-loved and successful, being described by the Birmingham Gazette as the ‘greatest comic singer in the world.’ His daughter started her music hall career after his death when she was ten years old. Minnie Cunningham tells us she began as a male impersonator and sang her father’s songs, although reviews of the time don’t mention male impersonation, only her singing and dancing. She moved from the provincial halls to London where she performed at the principal halls of the day. painter Walter Sickert by the poet and music hall critic Arthur Symons. Both men were smitten by the popular artiste and Sickert arranged to paint her portrait. The figure of Minnie Cunningham was painted from life in Sickert’s studio in Chelsea in 1892. For this painting she stood on a raised stand as if she were on stage but when asking her to pose for a later painting Sickert writes that he had built a proper stage ‘six foot square, with steps up to it.’ The background is thought to be the Tivoli on the Strand in London where Sickert had seen her perform. The painting was originally entitled, Miss Minnie Cunningham ‘I’m an old hand at love, though I’m young in years.’ This was one of her popular songs at the time and while singing it she dressed as a young girl which made the performance more daring. The painting became known as Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford. It was exhibited for the first time at the New English Art Club in 1892 to a mixed reception, with a reviewer in the Pall Mall Gazette writing ‘The red dress of Minnie Cunningham glows with refined richness in its setting, but the proportions of the figure and the feet and hands seem altogether absurd.’ The subject and setting were just too shocking for many at the time and it was said by some to represent degradation and vulgarity.

painter Walter Sickert by the poet and music hall critic Arthur Symons. Both men were smitten by the popular artiste and Sickert arranged to paint her portrait. The figure of Minnie Cunningham was painted from life in Sickert’s studio in Chelsea in 1892. For this painting she stood on a raised stand as if she were on stage but when asking her to pose for a later painting Sickert writes that he had built a proper stage ‘six foot square, with steps up to it.’ The background is thought to be the Tivoli on the Strand in London where Sickert had seen her perform. The painting was originally entitled, Miss Minnie Cunningham ‘I’m an old hand at love, though I’m young in years.’ This was one of her popular songs at the time and while singing it she dressed as a young girl which made the performance more daring. The painting became known as Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford. It was exhibited for the first time at the New English Art Club in 1892 to a mixed reception, with a reviewer in the Pall Mall Gazette writing ‘The red dress of Minnie Cunningham glows with refined richness in its setting, but the proportions of the figure and the feet and hands seem altogether absurd.’ The subject and setting were just too shocking for many at the time and it was said by some to represent degradation and vulgarity. contract in which she was engaged as principal girl in the Jack and Jill pantomime at £30 a week. She refused to wear the costume for her part saying it was too short and offended her standards of decency. Discussions with management were unsuccessful, often ending in tears. Eventually

contract in which she was engaged as principal girl in the Jack and Jill pantomime at £30 a week. She refused to wear the costume for her part saying it was too short and offended her standards of decency. Discussions with management were unsuccessful, often ending in tears. Eventually

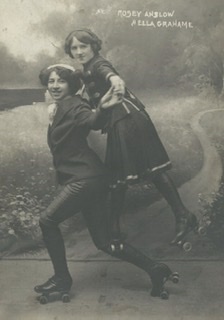

Dolly Mitchell was a young Scottish roller-skater who teamed up with her American teacher, Harley Davidson, to give displays in rinks and music halls. Advertised as the greatest skaters in the world and giving a wonderful exhibition of trick, fancy, acrobatic, graceful and artistic skating. They displayed over £1,000 worth of gold and diamond medals won in competition

Dolly Mitchell was a young Scottish roller-skater who teamed up with her American teacher, Harley Davidson, to give displays in rinks and music halls. Advertised as the greatest skaters in the world and giving a wonderful exhibition of trick, fancy, acrobatic, graceful and artistic skating. They displayed over £1,000 worth of gold and diamond medals won in competition and had this publicity photo taken by Léo Forbert’s studio in Warsaw. Ella writes on the back of the card ‘

and had this publicity photo taken by Léo Forbert’s studio in Warsaw. Ella writes on the back of the card ‘