If you saw yourself as a respectable person in 1851 you did not frequent the ‘Penny Gaff’ as described by Henry Mayhew in London Labour and the London Poor. It was a place of entertainment considered to be coarse and vulgar, which led to low morals in the young. The visitors, with few exceptions, were all boys and girls, whose ages seemed to vary from eight to twenty years. Some of the girls – though their figures showed them to be mere children – were dressed in showy cotton-velvet polkas, and wore dowdy feathers in their crushed bonnets. – – Some of them chose their partners and commenced dancing grotesquely, to the admiration of the lookers-on, who expressed their approbation in obscene terms – – that were received as compliments, and acknowledged with smiles and coarse repartees.

It’s not surprising that the music hall, a room usually attached to a pub in the early days, should inherit this reputation. Music hall owners and managers were keen to throw off this image and provided sumptuous surroundings and new acts to enhance respectability. There was a move to engage artistes from the ‘legitimate’ theatre and concert hall. They would rub shoulders with trick-cyclists, male impersonators and ventriloquists. Emily Soldene was ahead of the pack, appointed by Charles Morton to appear at the Oxford in the mid 1860s. She was a classically trained opera singer but was unable to secure the roles her manager expected hence he suggested she try the halls. Going to sing at a music hall was indeed a come-down. It hurt my artistic pride. Appearing as Miss Fitzhenry she sang operatic selections as well as patriotic songs which became popular with military and naval men. She appeared on a bill with Nellie Power, a pretty young girl who had a nice mother – – did a very fetching jockey song and dance. Making her name in music hall, Emily Soldene went on to star in opera-bouffe (French comic opera) and to manage her own company, travelling to Australia and settling there for some years before returning to England when she found herself in financial difficulty. In 1906 a benefit was held for her at the Palace Theatre which raised upwards of £800.

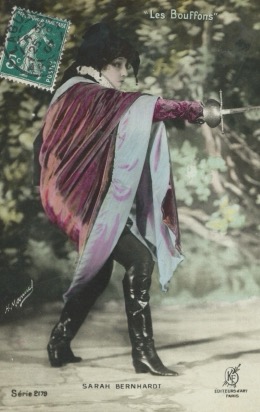

The great French actress, Sarah Bernhardt, accepted a month long contract from Oswald Stoll to appear at the London Coliseum in 1910 but had thought she was appearing in a ‘legitimate’ theatre. At first she was most unhappy about the engagement but by the time she arrived in England she had convinced herself that English music halls are so refined and she recognised the great intelligence of your music hall patron. Although her dramatic excerpts were in French the house was packed for every performance, with the telephone exchange unable to cope with the demand for advance tickets.

Almost thirty years before, in 1882, Sarah Bernhardt had failed to appear at a hall at the Blackpool Winter Garden. The Ulster Echo was of the opinion that the great actress was indignant at being asked to appear in a hall instead of at the theatre. She herself wrote I was suffering very much when I went to the theatre from a sore throat, which took away the greater part of my voice. I thought I was to play in a theatre, and not in a hall containing 15,000 persons. The managers told me to continue – – and they would be satisfied if they could only see me gesticulate. I am an artiste and not an exhibition. She did not continue and her tour came to an abrupt end.

Music halls were known to pay their successful artistes more than the legitimate theatre which could be an incentive for performers to ignore their moral compass and give audiences at the halls the benefit of their superior entertainment. It could also be the case that a performer who had not had success on the stage would try the halls which, in their minds, had lower standards and whose audiences would be impressed by their attempts at entertainment. In 1892, Miss Ida Ferrers, who had worked for some time in theatre, sued a theatrical agent for damages as he had failed to give her tuition or to get her a music hall engagement despite him receiving twenty shillings to do so. The defendant responded that the money was paid for him to provide three songs and to procure her a try-out at a music hall. He arranged a ‘show’ at the Trocadero where the band was present earlier than usual for her try-out. Miss Ferrers didn’t turn up because she had a bad throat. The agent gave her a letter of introduction at the Tivoli asking for a rehearsal but she was unable to sing the first note, despite encouragement, and later the manager at Gatti’s reported she was very amateurish in her singing. She was finally offered an engagement in the pantomime Humpty-Dumpty at Drury Lane but did not accept it. She said it was not enough money. Miss Ferrers did not win the case.

I’ll leave you with a description of performers from a ‘Penny Gaff’ written by Henry Mayhew. Presently one of the performers, with a gilt crown on his well-greased locks, descended from the staircase, his fleshings covered by a dingy dressing-gown, and mixed with the mob, shaking hands with old acquaintances. The ‘comic singer’ too, made his appearance among the throng – the huge bow to his cravat, which nearly covered his waistcoat, and the red end to his nose, exciting neither merriment or surprise.

Thanks to The British Newspaper Archive, London Labour and the London Poor – Henry Mayhew, My Theatrical and Musical Recollections – Emily Soldene, Monomania collection.