Jen Latona, real name Emma Jane Letty Carter, was born in 1881 in Birmingham. By the age of sixteen she was appearing in music halls under the name of Jennie Gabrielle. In January 1896 the Hull Daily Mail commented on her appearance at Hengler’s describing her as ‘the child musician, who possesses a singularly sweet and mellow soprano voice’. We learn from a review of her performance at the Palace Theatre in Edinburgh that she sang humorous songs and accompanied herself on the piano and concertina.

Jennie married an American performer twenty-five years her senior, born Benjamin Franklyn Titus, whose stage name was Frank Latona. Jennie Gabrielle became Jen Latona. Frank performed as a tramp musician, playing the trombone and a one-stringed fiddle, and included various effects in his act which he constucted himself. In a handwritten pencil note on a scrap of paper Frank reminds himself to ‘make whiskers to blow out and curl up – air pumps and rubber tube’.

Jen and Frank worked together as a double act with music, song, gags and repartee. In the archive of their work, presented to the Mayor of Lambeth by Jen Latona in her retirement, can be found handwritten sheets of ‘gags’, while jokes were often constructed from cut out newspaper articles. A handwritten notebook of sketches and gags contains this gem – ‘Why, that is the meanest man you ever saw. He is so mean he goes to the track and makes faces at the engineers so they will throw coal at him’. Newspaper personal ads were fair game too, with ‘Two girls want washing’ setting the standard. The couple performed extensively in New Zealand and the United States scribbling down material for their act on hotel notepaper and receiving offers of new songs from American songwriters.

When Frank Latona retired, Jen became a successful solo performer. She was on the bill with Vesta Tilley at the opening of the Croydon Hippodrome and was described as an ‘entertainer of exceptional merit’ to be compared with Margaret Cooper, a classically trained pianist who moved over to the music hall. However the writer quickly explains that Miss Cooper’s songs are of quite a different nature but that Jen is ‘a turn quite above the ordinary found at the halls’. Jen composed much of her stage music and the sheet music of the day shows she had a prolific repertoire with such songs as I’m going to buy you the R.I.N.G. and You can’t blame a Suffragette for that.

Frank died in 1930 and Jen retired a few years later. She lived in Streatham in London and when she died in 1955 her home and possessions were put up for auction, including a Schrieber grand piano and a souvenir programme of Sarah Bernhardt at the London Coliseum in 1913. The proceeds of the sale went to the Variety Artists Benevolent Fund.

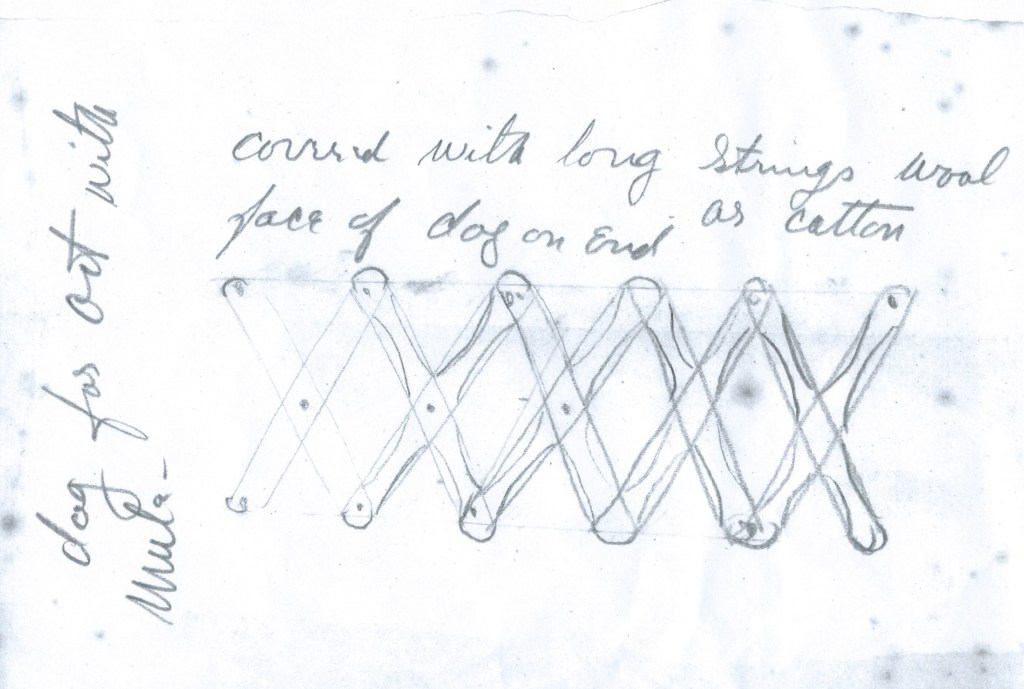

Frank had a genius for mechanical invention and invented and patented the Ednor Tank Washer. Of more interest to music hall fans here is a drawing in Frank’s hand of the workings of a dog to be used in an act with a mule.

We’ll leave the Latona’s with a final joke. ‘You are the most ignorant man I ever saw. Why, only yesterday I saw you giving hot water to the hens to make them lay hard-boiled eggs’. I hope you hear the echo of laughter.

Thanks to the British Newspaper Archive and Lambeth Archives. Images Monomania.

with a barrel organ. The card on the barrel organ reads ‘Molly O’Morgan’. The young woman is staring out from the photograph as if she has a story to tell. There is a story of Molly O’Morgan, the daughter of an Irish mother and an Italian organ-grinder father, who had dark brown hair and laughing eyes. It is said her mother died when Molly was young and she and her father left Ireland with a barrel organ and monkey to take their chances in Europe. Molly would dance while her father played the barrel organ and the crowds were charmed into parting with their coins. They travelled from city to city and eventually arrived in Monte Carlo where Molly’s fortunes changed. She was noticed by Duke Medici-Sinelli, an elderly widower, who naturally enough was also rich and charming. The Duke arranged for Molly to appear at a theatre and in the way of fairy tales she immediately became a star. Molly and the Duke married and unkind rumours suggested she was a gold-digger although the couple seemed devoted to each other. When the Duke died Molly did not marry again but came to Monte Carlo every year and stayed in the same suite in which she and the Duke had spent their honeymoon. She was said to live in Hungary with a distant branch of the Duke’s family.

with a barrel organ. The card on the barrel organ reads ‘Molly O’Morgan’. The young woman is staring out from the photograph as if she has a story to tell. There is a story of Molly O’Morgan, the daughter of an Irish mother and an Italian organ-grinder father, who had dark brown hair and laughing eyes. It is said her mother died when Molly was young and she and her father left Ireland with a barrel organ and monkey to take their chances in Europe. Molly would dance while her father played the barrel organ and the crowds were charmed into parting with their coins. They travelled from city to city and eventually arrived in Monte Carlo where Molly’s fortunes changed. She was noticed by Duke Medici-Sinelli, an elderly widower, who naturally enough was also rich and charming. The Duke arranged for Molly to appear at a theatre and in the way of fairy tales she immediately became a star. Molly and the Duke married and unkind rumours suggested she was a gold-digger although the couple seemed devoted to each other. When the Duke died Molly did not marry again but came to Monte Carlo every year and stayed in the same suite in which she and the Duke had spent their honeymoon. She was said to live in Hungary with a distant branch of the Duke’s family.

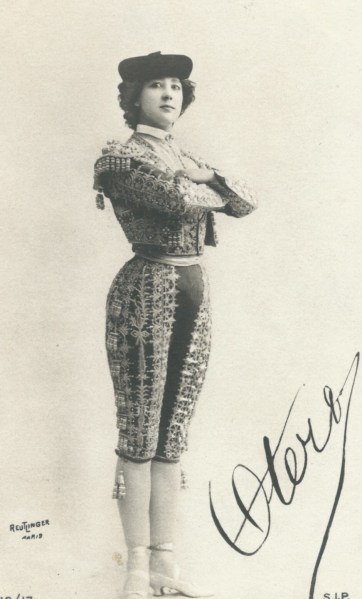

‘I was extraordinarily pretty’ states Caroline Otero in her autobiography My Story and this much is true. Music hall singer and dancer, courtesan and gambler, La Belle Otero lived a life of extremes and exaggerations that would raise eyebrows today. She claimed her mother was a beautiful Andalusian gypsy, Carmen, who danced, sang and told fortunes. Such was her beauty that a group of passers-by including a young Greek army officer, gazed at her in admiration as she was engaged in the unromantic task of hanging out the washing. The autobiography makes much of the courtship and devotion of the young man and tells of his death in a duel with Carmen’s lover. It is more likely La Belle Otero was born into a poor family in Galicia in November 1868 and given the name Augustina although she adopted the name Caroline at a young age. As a child she was sent away to work as a servant and is said to have been raped at the age of ten. It’s no wonder she gave herself a more romantic beginning.

‘I was extraordinarily pretty’ states Caroline Otero in her autobiography My Story and this much is true. Music hall singer and dancer, courtesan and gambler, La Belle Otero lived a life of extremes and exaggerations that would raise eyebrows today. She claimed her mother was a beautiful Andalusian gypsy, Carmen, who danced, sang and told fortunes. Such was her beauty that a group of passers-by including a young Greek army officer, gazed at her in admiration as she was engaged in the unromantic task of hanging out the washing. The autobiography makes much of the courtship and devotion of the young man and tells of his death in a duel with Carmen’s lover. It is more likely La Belle Otero was born into a poor family in Galicia in November 1868 and given the name Augustina although she adopted the name Caroline at a young age. As a child she was sent away to work as a servant and is said to have been raped at the age of ten. It’s no wonder she gave herself a more romantic beginning. who found her work as a dancer in a Café. She moved up the scale from theatre to theatre, starring at the Folies Bergère , collecting and discarding admirers and lovers. It is said men fought duels over her and left themselves penniless after showering the object of their affection with flowers and jewels. A writer in The Sketch in 1898 reports that Mdlle Otero came on to the Alhambra stage in a salmon-pink dress covered in diamonds and turquoises with her fingers heavy with rings, the dress setting off her pale complexion and black hair to great advantage. The diamonds, worth millions of francs, were tokens of the esteem in which she was held by her admirers. The writer goes on to say that ‘most performers humbly seek the suffrages of their audience; La Belle Otero, whose equipment is in many respects inferior, from the artistic point of view, to that of her competitors, demands them as a right.’

who found her work as a dancer in a Café. She moved up the scale from theatre to theatre, starring at the Folies Bergère , collecting and discarding admirers and lovers. It is said men fought duels over her and left themselves penniless after showering the object of their affection with flowers and jewels. A writer in The Sketch in 1898 reports that Mdlle Otero came on to the Alhambra stage in a salmon-pink dress covered in diamonds and turquoises with her fingers heavy with rings, the dress setting off her pale complexion and black hair to great advantage. The diamonds, worth millions of francs, were tokens of the esteem in which she was held by her admirers. The writer goes on to say that ‘most performers humbly seek the suffrages of their audience; La Belle Otero, whose equipment is in many respects inferior, from the artistic point of view, to that of her competitors, demands them as a right.’  Otero was adept at self publicity and in 1902 the Paris correspondent of the Express writes that an engineer in Brussels was constructing an airship for her ‘by means of which she hopes to make a triumphal entry next August into Biarritz.’ She was worried it could be dangerous and so the balloon was to be dragged along by a car attached by a thin wire. If there was an accident she could ‘descend to the car by means of a rope ladder, which she will have tied in to the airship. The airship will float gracefully above the automobile at a height of 100ft.’ Mistress to ambassadors, princes, including the future Edward VII, and nobility throughout Europe, La Belle Otero scandalised and fascinated society in equal measure. Her weakness was gambling and she lost vast sums of money at the tables, sometimes her own and often her admirers’ fortunes. The Tatler tells us that in 1909 police raided a gambling club in Paris and found fifty women and ten men. On further investigation another woman, Caroline Otero, was found in a cupboard.

Otero was adept at self publicity and in 1902 the Paris correspondent of the Express writes that an engineer in Brussels was constructing an airship for her ‘by means of which she hopes to make a triumphal entry next August into Biarritz.’ She was worried it could be dangerous and so the balloon was to be dragged along by a car attached by a thin wire. If there was an accident she could ‘descend to the car by means of a rope ladder, which she will have tied in to the airship. The airship will float gracefully above the automobile at a height of 100ft.’ Mistress to ambassadors, princes, including the future Edward VII, and nobility throughout Europe, La Belle Otero scandalised and fascinated society in equal measure. Her weakness was gambling and she lost vast sums of money at the tables, sometimes her own and often her admirers’ fortunes. The Tatler tells us that in 1909 police raided a gambling club in Paris and found fifty women and ten men. On further investigation another woman, Caroline Otero, was found in a cupboard.