Nelly Power

Merry Nelly Power was born in 1854 and according to an article in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News started out on stage in 1863 at the Southampton Music Hall which was owned by her uncle. Her charm and vivacity carried her to success in the provinces and London, where she entertained in pantomime and burlesque. In those days burlesque was a drama, usually with song and dance, which spoofed serious productions and made fun of the politics of the day. The topical references would often change from one performance to another and there were often exchanges between the actors and the audience. The risqué element was provided by women playing the part of men, dressed in tights and short trousers and sometimes smoking. The costumes were embellished with feathers, silks and fringes.

In 1867 Nelly was appearing at the London Metropolitan Music Hall in the Edgware Road with no star billing but by 1870 she was in the Four-Leaved Shamrock at the Canterbury Hall in London. The advertisement in The Sportsman tells us she is appearing every evening in the Grand Ballet, as Dermot, as the Pet Jockey and as Apollo. She also gave her celebrated imitations of the most popular songs of the day. She is obviously a big draw as the management is keen to point out prices will not rise during the engagement of this charming burlesque actress and the advertisement is devoted solely to Nelly. Here are two photos of burlesque costumes from the 1870s.

Augustus Harris engaged her as principal boy in pantomime and the up and coming Vesta Tilley had her nose put slightly out of joint when she realised she was to play second fiddle to Nelly and also to be her understudy. In her recollections, Vesta makes the best of it, commanding a high salary and having a scene to herself to sing one of her popular songs. She points out, ‘It was the one and only time I had played second fiddle’ while acknowledging Nelly Power was a great star in those days.

In 1874 Nelly married Israel Barnett who seems to have been an unscrupulous character and the marriage was not a happy one. In 1875 Nelly’s admirer, Frederick Hobson, was charged with assaulting Barnett who was by now living at an hotel in Covent Garden while Nelly lived with her mother in Islington. Nelly was filing for a divorce but Barnett hoped for a reconciliation and was upset to find Nelly in Hobson’s company on several occasions. From the reports of the trial we find out that Barnett had been involved in dodgy financial dealings and had spent a brief time in prison. He was unable to remember if there were any charges of fraud against him but did remember he was a bankrupt. Nelly gave a strange statement in which she said since she had known Barnett all her jewellery had been ‘swept away’ . Hobson was bound over to be of good behaviour for six months on a bond of £50. Nelly’s statement made more sense when I came across a report of a theft of jewellery from her home to the value of £1,500 in 1874. There was no evidence of a break-in and the theft was described as mysterious.

La-di-dah!

Nelly made a name for herself as an early male impersonator wearing tights, spangles and a curly-brimmed hat. She had a great hit with a song entitled La-di-dah which made fun of the swells of the day.

Ee is something in an office, lardy dah!

And he quite the city toff is, lardy dah!

It seems that females didn’t wear authentic male attire in the early days of male impersonation and Nelly may have been adapting a burlesque costume.

She faded for a while, suffering ill health, but in 1885 was appearing at three London music halls nightly and was said to retain all her old go. She died two years later, performing to the end, but there was no money to pay for the funeral. A subscription was got up to pay the undertaker but in the following year her agent, George Ware, was sued for £18 19s 6d as the full funeral costs had not been met. Not long after Nelly’s death her mother Agnes was taken to court by a draper who claimed £4 4s 3d for various articles supplied to the deceased in 1885 and 1886. These included bonnets, underclothing, gloves, fancy aprons, dress materials etc. The judge remarked that there was no money even to pay for the funeral and found for Mrs Power. Nelly’s greatest hit was ‘The Boy in the Gallery’ adopted cheekily and successfully by rising star Marie Lloyd.

Nelly Power was buried in Abney Park Cemetery in north London and her funeral procession was attended by at least three thousand people. The British Music Hall Society restored her neglected grave in 2001 and the inscription reminds us she was only thirty-two when she died.

NOTE – on some devices the last illustration of Nelly Power in male impersonator costume is showing upside down. I have tried to rectify this to no avail, so many apologies if she is standing on her head in your version.

Thanks to the British Newspaper Archive, Michael Kilgarriff, Recollections of Vesta Tilley

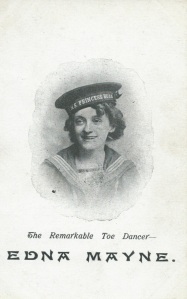

Edna Mayne is described as the Rembarkable Toe Dancer and in January 1911 we find her at the Palace Theatre, Gloucester, in Puss in Boots. She is described as an exceedingly clever sand dancer while her work on her toes was said to be very smart. A sand dance has been described as an eccentric dance with exaggerated movements while dressed in an approximation of Egyptian style.

Edna Mayne is described as the Rembarkable Toe Dancer and in January 1911 we find her at the Palace Theatre, Gloucester, in Puss in Boots. She is described as an exceedingly clever sand dancer while her work on her toes was said to be very smart. A sand dance has been described as an eccentric dance with exaggerated movements while dressed in an approximation of Egyptian style.

Daisy Jerome was born in the States in 1888 but moved to England as a child when her father suffered a financial crisis. Money was needed and she followed her sister on to the stage. She was a small, dainty figure with bright red hair, compelling eyes and an expressive face. Her appearance belied her risqué performances and her hoarse, sensual voice. She was a toe-dancer and a wooden shoe dancer, but best known as a mimic and comic singer. Daisy married Frederick Fowler in 1906 but they lived together for less than a year with Fowler blaming the marriage breakdown on the constant presence of his mother-in-law. He filed for divorce on the grounds of Daisy’s misconduct. She was living with Mr Cecil Allen in Battersea by this time and claimed Allen would marry her if she was divorced. The decree nisi was granted with Fowler saying he would shoot Allen if he didn’t marry Daisy. She left for a three year tour of Australia shortly after accompanied only by her mother. She adopted the name ‘the electric spark‘ and seems to have lived up to this in her public and private life.

Daisy Jerome was born in the States in 1888 but moved to England as a child when her father suffered a financial crisis. Money was needed and she followed her sister on to the stage. She was a small, dainty figure with bright red hair, compelling eyes and an expressive face. Her appearance belied her risqué performances and her hoarse, sensual voice. She was a toe-dancer and a wooden shoe dancer, but best known as a mimic and comic singer. Daisy married Frederick Fowler in 1906 but they lived together for less than a year with Fowler blaming the marriage breakdown on the constant presence of his mother-in-law. He filed for divorce on the grounds of Daisy’s misconduct. She was living with Mr Cecil Allen in Battersea by this time and claimed Allen would marry her if she was divorced. The decree nisi was granted with Fowler saying he would shoot Allen if he didn’t marry Daisy. She left for a three year tour of Australia shortly after accompanied only by her mother. She adopted the name ‘the electric spark‘ and seems to have lived up to this in her public and private life.

Adelaide Gray came to this country from Australia with her son, Oswald, after the death of her husband. She married John Stoll who was the owner of the Parthenon Rooms in Liverpool and took over the venue shortly after John’s death in 1880. The Parthenon Music Hall was born. Adelaide was helped by fourteen year old Oswald who looked after the artistes backstage, eventually putting together the programme and booking the acts.

Adelaide Gray came to this country from Australia with her son, Oswald, after the death of her husband. She married John Stoll who was the owner of the Parthenon Rooms in Liverpool and took over the venue shortly after John’s death in 1880. The Parthenon Music Hall was born. Adelaide was helped by fourteen year old Oswald who looked after the artistes backstage, eventually putting together the programme and booking the acts. The contract I have is for two artistes and the weekly salary is four pounds ten shillings between them so any fine would severely damage them financially. The contract is signed by Adelaide and Oswald Stoll.

The contract I have is for two artistes and the weekly salary is four pounds ten shillings between them so any fine would severely damage them financially. The contract is signed by Adelaide and Oswald Stoll.

The name Harry Gordon Selfridge, founder of the London department store, was linked to some of the most popular and sought after women of the day. His generosity towards them knew no bounds and age did not diminish his enthusiasm for being seen in their company. In the early 1920s Mr Selfridge saw a performance by the Dolly sisters and was immediately struck by the beauty and talent of Jenny Dolly. I’ve never understood why he chose Jenny on sight alone as the Dolly sisters were identical twins. Jenny and Rosie Dolly, birth names Yansci and Roszika Deutsch, were born in Hungary and moved to the States when they were twelve, beginning a dancing career in the theatre that would make them household names in Europe as well as America. They started in vaudeville making up their own dances, their mother putting together the costumes, and gradually got themselves noticed with their liveliness and enthusiasm although their singing seems to have been mediocre. They had that indefinable something made even more special by the fact that they were identical twins.

The name Harry Gordon Selfridge, founder of the London department store, was linked to some of the most popular and sought after women of the day. His generosity towards them knew no bounds and age did not diminish his enthusiasm for being seen in their company. In the early 1920s Mr Selfridge saw a performance by the Dolly sisters and was immediately struck by the beauty and talent of Jenny Dolly. I’ve never understood why he chose Jenny on sight alone as the Dolly sisters were identical twins. Jenny and Rosie Dolly, birth names Yansci and Roszika Deutsch, were born in Hungary and moved to the States when they were twelve, beginning a dancing career in the theatre that would make them household names in Europe as well as America. They started in vaudeville making up their own dances, their mother putting together the costumes, and gradually got themselves noticed with their liveliness and enthusiasm although their singing seems to have been mediocre. They had that indefinable something made even more special by the fact that they were identical twins. The Dollies appeared in the Ziegfeld Follies and in films, trying solo careers and then getting back together. They came to Europe in 1920 and wowed London audiences with their costumes and their style. By this time they had learned that sumptuous costumes and stage sets put them in the public eye and made them memorable. This together with their vitality and sheer personality made up for the fact that they were not the greatest singers and dancers. They were popular backstage, being generous and friendly towards ordinary theatre workers. During their stay in the capital they were thrilled to be taken up by London society, dancing with Edward, Prince of Wales and attending parties thrown by the rich and famous.

The Dollies appeared in the Ziegfeld Follies and in films, trying solo careers and then getting back together. They came to Europe in 1920 and wowed London audiences with their costumes and their style. By this time they had learned that sumptuous costumes and stage sets put them in the public eye and made them memorable. This together with their vitality and sheer personality made up for the fact that they were not the greatest singers and dancers. They were popular backstage, being generous and friendly towards ordinary theatre workers. During their stay in the capital they were thrilled to be taken up by London society, dancing with Edward, Prince of Wales and attending parties thrown by the rich and famous. The Dolly Sisters moved to Paris and were equally popular there. They had become aware of their own worth and in 1926 they sued the management of the Moulin Rouge Music Hall for 500,000 francs for breach of contract. They were unhappy that Mistinguett, a famous revue star, was topping the bill. The Moulin Rouge management counter-sued for the same amount of money as the Dolly Sisters had walked off in the middle of a rehearsal and joined the cast of the Casino de Paris. They won their case and were awarded the full amount of damages plus costs. They became members of the smart set, gambling in Deauville and following the social season. They were known for arriving at the casino dripping in jewels, gifts from wealthy admirers, and gambling vast amounts of money, often bank-rolled by those same wealthy individuals.

The Dolly Sisters moved to Paris and were equally popular there. They had become aware of their own worth and in 1926 they sued the management of the Moulin Rouge Music Hall for 500,000 francs for breach of contract. They were unhappy that Mistinguett, a famous revue star, was topping the bill. The Moulin Rouge management counter-sued for the same amount of money as the Dolly Sisters had walked off in the middle of a rehearsal and joined the cast of the Casino de Paris. They won their case and were awarded the full amount of damages plus costs. They became members of the smart set, gambling in Deauville and following the social season. They were known for arriving at the casino dripping in jewels, gifts from wealthy admirers, and gambling vast amounts of money, often bank-rolled by those same wealthy individuals. It is hard to imagine that the Dollies had anything other than a happy ending but sadly this was not the case. The world they knew was disappearing and other stars were taking the stage. Jenny never fully recovered psychologically or physically from her dreadful car accident and committed suicide. Rosie lived for almost thirty years without her sister. In an interview in the 1960s Rosie Dolly said, ‘I found out that America has changed— I’m in New York, old friends you call up when you arrive – they’ve forgotten you. They don’t call back.’

It is hard to imagine that the Dollies had anything other than a happy ending but sadly this was not the case. The world they knew was disappearing and other stars were taking the stage. Jenny never fully recovered psychologically or physically from her dreadful car accident and committed suicide. Rosie lived for almost thirty years without her sister. In an interview in the 1960s Rosie Dolly said, ‘I found out that America has changed— I’m in New York, old friends you call up when you arrive – they’ve forgotten you. They don’t call back.’